How Did Pasteur Finally Disprove Spontaneous Generation?

Have you ever wondered why people once believed that life could just pop out of non-living matter like mice suddenly appearing from old cheese or maggots showing up on spoiled meat? This belief was known as the spontaneous generation theory. In simple terms, it claimed that living organisms could arise from non-living materials in everyday surroundings. Over the centuries, many scientists tested and questioned this idea. Eventually, new experiments showed that life only comes from existing life forms, not from lifeless objects. Let us understand how spontaneous generation was proposed, challenged and finally disproved.

Aristotle’s Work

The spontaneous generation theory was given by the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BCE). He noticed that certain small organisms appeared suddenly in places where life was not expected, such as maggots on rotting meat. Aristotle believed that if matter contained something he called “vital heat,” living creatures could grow from non-living substances. This idea was also known as Aristotle's spontaneous generation and remained widely accepted for almost 2,000 years.

What is the Spontaneous Generation Theory?

According to the spontaneous generation theory, living beings, especially smaller organisms, come directly from non-living things under the right conditions. For instance:

Mice supposedly appeared out of a mixture of cheese and bread left in a corner.

Maggots seemed to come from dead meat. These spontaneous generation examples were once considered undeniable proofs, although we now understand them as incorrect interpretations of natural processes.

Early Experiments: From Redi to Spallanzani

Francesco Redi’s Work (1668)

Francesco Redi, an Italian naturalist, challenged the idea that maggots arose spontaneously on decaying meat. He placed pieces of meat in different jars:

Two jars were covered with gauze,

Two jars were sealed with corks,

Two jars were left open.

In the open jars, flies laid eggs on the meat, and maggots later appeared. In covered or sealed jars, no maggots formed. This showed that maggots came from fly eggs, not from the meat itself.

Pier Antonio Micheli’s Observation (1729)

Pier Antonio Micheli, an Italian botanist, carried out experiments with fungal spores on melon slices. He noticed that when he placed known spores on melon, the same type of fungus would grow. This provided further evidence against the idea of organisms suddenly emerging without any parent source.

John Needham’s Experiment (1745)

John Needham, an English biologist, boiled a broth containing plant and animal matter, sealed it, and observed that microscopic organisms still appeared. He argued that this supported spontaneous generation. However, his heating methods were not sufficient to kill all the microorganisms, which led to the misleading conclusion.

Lazzaro Spallanzani’s Experiment (1768)

Lazzaro Spallanzani improved Needham’s method by boiling the broth much more thoroughly. He sealed one flask and left another open to the air. The sealed flask showed no growth of microorganisms, while the open flask had plenty of microbial life. Spallanzani concluded that exposure to air brought in microbes and was responsible for the growth in the broth, again challenging the idea of spontaneous generation.

By then, scientific doubt about spontaneous generation was steadily growing.

How Louis Pasteur Disproved the Theory of Spontaneous Generation

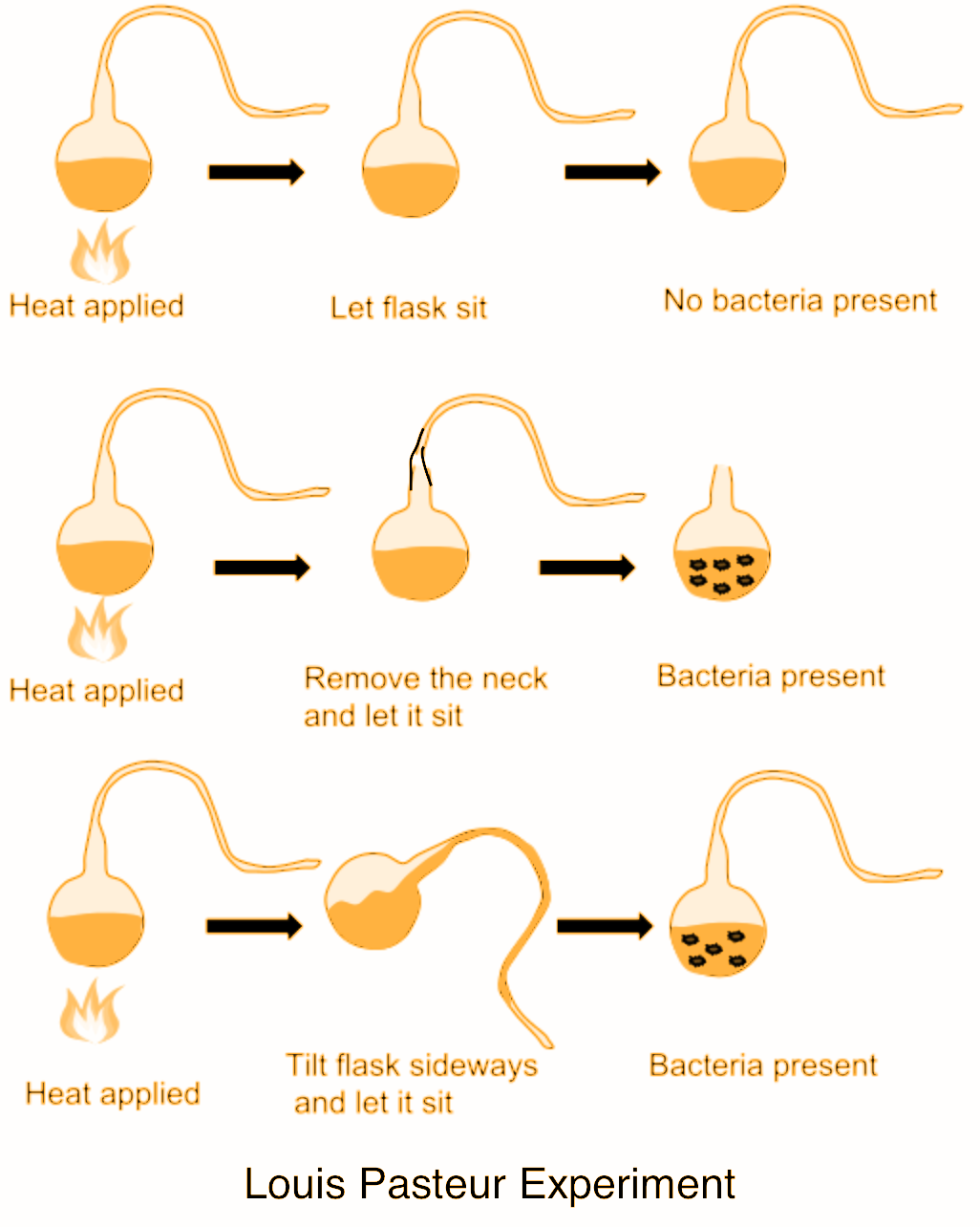

Who disproved the theory of spontaneous generation in a definitive way? In 1859, Louis Pasteur’s spontaneous generation experiment settled the debate once and for all. Pasteur used flasks with long, curved necks (called “swan-neck flasks”) and boiled meat broth inside them. These flasks allowed fresh air to enter but trapped dust and microbes in the neck’s curve. As a result:

The broth stayed clear for a long time because no microorganisms could reach it.

Only when the flasks were tilted, or the necks broken did the broth become cloudy with microbial growth.

Pasteur showed that no life appeared in the broth unless living microbes from the outside were allowed to enter. His famous statement, “Omne vivum ex vivo” (“All life from life”), underlined that new life forms originate from existing life.

John Tyndall’s Contribution

John Tyndall, an Irish physicist, further strengthened Pasteur’s findings by demonstrating how tiny particles in the air (including microbes) could be removed through careful processes. He also studied the heat resistance of certain spores. Tyndall’s work helped confirm that spontaneous generation did not occur, reinforcing the conclusion drawn from Louis Pasteur's spontaneous generation experiments.

Spontaneous Generation vs. Cell Theory

While spontaneous generation suggests life can come from non-living matter, modern cell theory states that:

All living organisms are made up of one or more cells.

The cell is the basic unit of structure and function in living organisms.

All new cells come from existing cells.

In other words, life originates only from life—a concept that fully replaced the idea of spontaneous generation.

Quick Quiz (with Answers)

Which philosopher’s observations led to the spontaneous generation theory?

a) Plato

b) Aristotle

c) Socrates

d) AnaximenesAnswer: b) Aristotle

Who disproved the theory of spontaneous generation with his swan-neck flask experiment?

a) John Tyndall

b) Francesco Redi

c) Louis Pasteur

d) Lazzaro SpallanzaniAnswer: c) Louis Pasteur

Which scientist proved that maggots came from fly eggs, not from rotting meat?

a) John Needham

b) Pier Antonio Micheli

c) Lazzaro Spallanzani

d) Francesco RediAnswer: d) Francesco Redi

According to Aristotle, spontaneous generation, which substance was believed to have “vital heat”?

a) Air

b) Earth

c) Non-living matter

d) WaterAnswer: c) Non-living matter

Related Topics

FAQs on Spontaneous Generation: Origins, Experiments, and Scientific Rejection

1. What exactly is the theory of spontaneous generation?

The theory of spontaneous generation, also known as abiogenesis in its historical context, was the old belief that living organisms could arise directly from non-living matter. For instance, people thought that mice could be created from old rags and wheat, or that maggots could appear from rotting meat on their own.

2. Who first came up with the idea of spontaneous generation?

The idea dates back to ancient times and was systematically explained by the Greek philosopher Aristotle. He proposed that life could form from non-living material if it contained 'pneuma' or 'vital heat'. For example, he believed aphids arose from the dew on plants.

3. How did Francesco Redi's experiment first challenge this theory?

In the 17th century, Italian scientist Francesco Redi conducted a simple but crucial experiment. He placed meat in three separate jars: one open, one sealed, and one covered with gauze. Maggots only appeared in the open jar where flies could land. This showed that the maggots came from flies (pre-existing life), not from the meat itself.

4. What was Louis Pasteur's famous experiment that finally disproved spontaneous generation?

Louis Pasteur used special swan-neck flasks containing a sterilised nutrient broth. The S-shaped neck allowed air to enter but trapped airborne dust and microbes in its bend. The broth remained clear and free of life. However, when the flask was tilted to let the broth touch the trapped dust, it quickly became cloudy with microbial growth, proving that organisms came from other organisms in the air, not the broth itself.

5. What is the main difference between spontaneous generation and biogenesis?

The two theories are direct opposites. Spontaneous generation claims that life can come from non-life. In contrast, the theory of biogenesis states that all life can only come from pre-existing life ('omne vivum ex vivo'). Modern biology is founded on the principle of biogenesis.

6. If the evidence against it was so clear, why did the theory of spontaneous generation last for so long?

The theory persisted for over 2,000 years mainly because people lacked the tools to see microorganisms. Without microscopes, the sudden appearance of mould, maggots, or microbes seemed magical and was easily explained by spontaneous generation. It took carefully designed experiments by scientists like Redi, Spallanzani, and Pasteur to provide conclusive evidence against it.

7. How did disproving spontaneous generation impact the field of science and medicine?

Disproving this theory was a monumental step in biology and medicine. It paved the way for modern cell theory and the germ theory of disease. Understanding that germs come from other germs led to crucial practices like sterilisation, pasteurisation, antiseptic surgery, and public health measures that have saved countless lives.