Electronic Configuration: An Introduction

Have you ever considered how atoms are represented? The number of orbitals for atoms with a high atomic number is also high. For instance, the atomic number of mercury (Hg) is 80. For example, mercury (Hg) has an atomic number of 80. The filling of electrons is somewhat complicated as it has 80 electrons to fill around the nucleus. We must deal with a few electronic configuration prediction rules in order to specify the position of an electron in an atom.

Electronic configuration is defined as the layered arrangement of shells, where a specific number of electrons orbit around the nucleus. An atom has a central core where the entire positive charge concentrates; this is the nucleus. The nucleus contains neutrons and protons huddled closely right at the centre of the atom. Atomic shells have a layered arrangement. Each shell has a fixed number of electrons revolving around the nucleus.

A scientist named Charles Bury gave a set of simple rules that made it very easy to understand how electrons are arranged in Bohr's atomic model. This scheme of electron arrangement is known as the Bohr-Bury electron arrangement.

Rules for Filling Electrons

Rules for filling electrons based on Bohr-Bury electron arrangement are given as follows:

An electron will always fill an orbit or a shell with lower energy and then occupy the higher energy ones. Therefore, electron filling starts from the K shell, then the L, M, and N accordingly.

Depending on the orbit number, each orbit can only hold a finite number of electrons. The formula can determine this.

Number of electrons = 2n2

where n is the orbit number. Thus, this rule is frequently referred to as the "2n2 rule". The number of electrons that each orbit can hold increases with respect to its 'n' value.

Shells and Subshells

The shells are the paths around the nucleus where the electrons move. The shell nearest to the nucleus has lower energy. The energy increases as it travels to the outermost shell. It can be denoted as K, L, M, N, etc. Subshells are seen within the shells, which serve as the paths of electrons. The names of the subshells are based on the quantum number of angular momentum. A shell has four different subshell types: s, p, d, and f. The lowest energy subshell is the s, followed by p, d, and f. The formula 2(2l+1) can be used to determine the maximum number of electrons that can be occupied by each subshell. As a result, the s, p, d, and f subshells should be able to hold 2, 6, 10, and 14 electrons, respectively.

Number of Electrons Occupied in Each Shell

The maximum number of electrons that the outermost shell of an atom can possess is eight. This is called the octet rule. Having the eight electrons in the outermost shell makes the atom stable. The outermost shell is also termed as the valence shell. The electrons occupied in the valence shell are called valence electrons.

Electronic Configuration of Atoms

Now let's put these rules to work and figure out the electronic configurations for some elements. For example, magnesium has an atomic number of 12. According to the first rule, the K shell is filled first as it is the lowest in energy. Only 2 out of 12 electrons are filled in the K shell. As a result, the second rule is also followed, because the K shell can only hold a fixed number of electrons, namely two. Now there is a balance of 10 electrons. As per the third rule, the valence shell, which is the L shell here, cannot hold more than 8 electrons. So out of 10, 8 electrons enter the L shell and the remaining 2 electrons enter the M shell. Hence, the M shell becomes the valence shell.

Electronic Configuration of Some Elements

Electronic Configuration of Ions

The electronic configuration for ions is similar to that of atoms. The electronic configuration of a cation can be found out by removing electrons from the valence shells. Similarly, the electronic configuration of anions can be found by adding electrons to the valence shells.

For example, Mg has an atomic number of 12. The electronic configuration of Mg is

Mg: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2

For Mg2+, the electronic configuration can be written by removing 2 electrons from the valence shell, that is, 3s. Hence, the electronic configuration becomes

Mg2+: 1s2 2s2 2p6

Similarly, for Cl-, the atomic number is 17, with the electron configuration is

Cl: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p5

To write the electronic configuration of cl-anion, we have to add one electron to the outermost shell, 3p.

Cl-: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6.

In this way, we can predict the electronic configuration of any ion.

Electronic Configuration Diagram

Electrons are arranged into energy levels or shells around the nucleus of an atom. The orbital radius increases as the energy level increases. We depict the shell by drawing a circle. A dot or a cross represents each electron and represents the nucleus by the chemical symbol. Each electron in an atom is in a particular shell, and the electron must occupy the lowest available shell nearest the nucleus. So, when we draw the electronic configuration, we have to fill up each shell in turn, starting with the lowest.

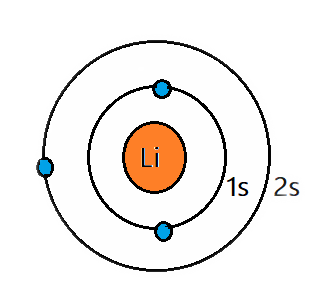

Let’s take lithium as an example.

Lithium Electron Structure

Lithium has an atomic number of 3. It has 3 electrons and 3 protons - first electron into the first shell. And the second electron goes to the same shell. However, this shell can only contain a maximum of 2 electrons. So, the third element must fill in the next shell. This same process of filling electrons applies to even larger atoms too. The filling of electrons should be from the lowest to the highest energy levels.

Interesting Facts

Have you ever wondered why atomic shells are represented by the letters K, L, M, N, etc. instead of using A, B, C, etc. This is because of the fact that, at that point of time, only some orbitals were discovered. Scientists wanted to be certain that there was room to add more orbits inside and outside of the existing ones.

Key Features

An electronic configuration is the arrangement of electrons in an atom in a particular manner in the shells.

It follows the Bohr-Bury scheme to fill the electrons in the orbits.

A lower-energy orbit or shell will always be filled by an electron before moving on to a higher-energy orbit or shell.

According to the 2n2 rule, only a fixed number of electrons can be filled in each orbit, where n is the number of the orbit.

The maximum number of electrons that the outermost shell of an atom can contain is 8.

FAQs on Electronic Configuration of Atoms and Ions

1. What is meant by the electronic configuration of an atom?

The electronic configuration of an atom describes the specific arrangement and distribution of its electrons within different energy levels, or shells, and their respective subshells and orbitals. It provides a systematic way to represent which orbitals contain electrons. For example, the electronic configuration of Helium (atomic number 2) is written as 1s², indicating that both of its electrons are in the 's' orbital of the first energy shell.

2. What are the fundamental rules for filling electrons into atomic orbitals?

The distribution of electrons into orbitals follows three main rules to ensure the atom is in its most stable, or ground, state:

- Aufbau Principle: Electrons first occupy the orbitals with the lowest energy available before moving to higher energy orbitals. The energy is generally determined by the (n+l) rule.

- Pauli Exclusion Principle: An atomic orbital can hold a maximum of two electrons, and these two electrons must have opposite spins (one spin up, one spin down).

- Hund's Rule of Maximum Multiplicity: When filling orbitals of equal energy (degenerate orbitals), electrons will fill each orbital singly before any orbital gets a second electron. All singly occupied orbitals will have electrons with the same spin.

3. How do you write the electronic configuration for an atom and its ion?

To write an electronic configuration, follow these steps:

- Find the element's atomic number (Z), which equals the number of electrons in a neutral atom.

- Fill the electrons into subshells according to the Aufbau principle (e.g., 1s, 2s, 2p, 3s, 3p, 4s, 3d...).

- For a cation (positive ion), write the configuration for the neutral atom first, then remove the required number of electrons from the orbital with the highest principal quantum number (n), which is the outermost shell.

- For an anion (negative ion), add the required number of electrons to the outermost available orbital according to the rules.

For example, for a Fluoride ion (F⁻), first write the config for neutral F (Z=9): 1s²2s²2p⁵. Then add one electron to get F⁻: 1s²2s²2p⁶.

4. Why do Chromium (Cr) and Copper (Cu) have exceptional electronic configurations?

Chromium (Cr, Z=24) and Copper (Cu, Z=29) are notable exceptions to the Aufbau principle due to the enhanced stability of half-filled and fully-filled d-orbitals.

- For Chromium (Cr), the expected configuration is [Ar] 4s²3d⁴. However, the actual configuration is [Ar] 4s¹3d⁵. An electron moves from the 4s orbital to the 3d orbital to achieve a more stable, half-filled d-subshell (d⁵).

- For Copper (Cu), the expected configuration is [Ar] 4s²3d⁹. The actual configuration is [Ar] 4s¹3d¹⁰, as a fully-filled d-subshell (d¹⁰) is more stable.

This extra stability arises from symmetrical electron distribution and increased electron exchange energy.

5. How does an element's electronic configuration determine its position in the periodic table?

The electronic configuration is the foundation of the periodic table's structure:

- The Period Number corresponds to the principal quantum number (n) of the outermost or valence shell. For example, Sodium ([Ne] 3s¹) is in Period 3 because its valence electron is in the n=3 shell.

- The Block (s, p, d, f) is determined by the subshell that receives the last electron. For instance, Aluminium ([Ne] 3s²3p¹) is a p-block element.

- The Group Number is related to the number of valence electrons, which directly influences the element's chemical properties.

6. What are the electronic configurations of Fe²⁺ and Fe³⁺ ions, and which one is more stable?

First, the configuration of a neutral Iron atom (Fe, Z=26) is [Ar] 4s²3d⁶.

- To form the Fe²⁺ ion, two electrons are removed from the outermost shell, which is the 4s orbital. So, the configuration for Fe²⁺ is [Ar] 3d⁶.

- To form the Fe³⁺ ion, a third electron is removed. This electron comes from the 3d orbital, resulting in the configuration [Ar] 3d⁵.

The Fe³⁺ ion is more stable than the Fe²⁺ ion. This is because its 3d subshell is exactly half-filled (3d⁵), an arrangement that provides extra stability due to symmetrical electron distribution.

7. What is the core difference between an 'orbit' in the Bohr model and an 'orbital' in the modern quantum mechanical model?

The terms 'orbit' and 'orbital' describe two very different concepts:

- An orbit, as proposed by Niels Bohr, is a well-defined, two-dimensional circular path around the nucleus in which an electron was thought to revolve. This concept is considered outdated as it violates the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle.

- An orbital, according to the quantum mechanical model, is a three-dimensional region of space around the nucleus where the probability of finding an electron is maximum (typically >90%). It does not define a fixed path but rather a probability cloud with a specific shape (e.g., s-orbitals are spherical, p-orbitals are dumbbell-shaped).